Entering Pioneer Village in the amusement park of Lagoon, located in Farmington, Utah, one can see a small building immediately to the left, nestled up against the water slide area. Inside that building is a collection of tokens, currency, and other artifacts from Utah’s history.

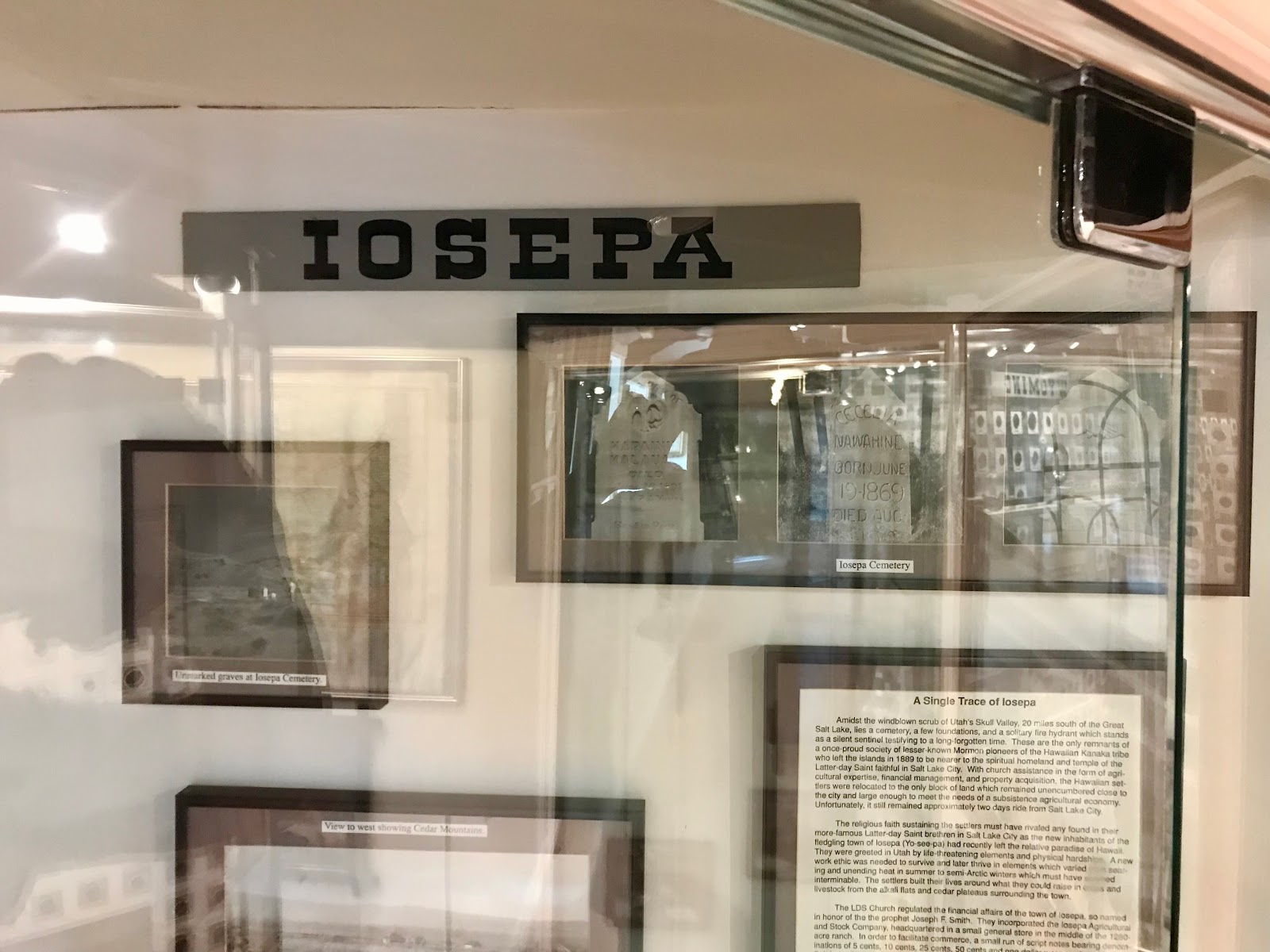

In the far left corner is a display case entitled, “Iosepa.”

A description inside the case reads:

A Single Trace of Iosepa

Amidst the windblown scrub of Utah's Skull Valley, 20 miles south of the Great Salt Lake, lies a cemetery, a few foundations, and a solitary fire hydrant which stands as a silent sentinel testifying to a long-forgotten time. These are the only remnants of a once-proud society of lesser-known Mormon pioneers of the Hawaiian Kanaka tribe who left the islands in 1889 to be nearer to the spiritual homeland and temple of the Latter-day Saint faithful in Salt Lake City. With church assistance in the form of agricultural expertise, financial management, and property acquisition, the Hawaiian settlers were relocated to the only block of land which remained unencumbered close to the city and large enough to meet the needs of a subsistence agricultural economy. Unfortunately, it still remained approximately two days' ride from Salt Lake City.

The religious faith sustaining the settlers must have rivaled any found in their more-famous Latter-day Saint brethren in Salt Lake City as the new inhabitants of the fledgling town of losepa had recently left the relative paradise of Hawaii. They were greeted in Utah by life-threatening elements and physical hardships. A new work ethic was needed to survive and later thrive in elements which varied from searing and unending heat in summer to semi-Arctic winters which must have seemed interminable. The settlers built their lives around what they could raise in crops and livestock from the alkali flats and cedar plateaus surrounding the town.

The LDS Church regulated the financial affairs of the town of losepa, so named in honor of the prophet Joseph F. Smith. They incorporated the losepa Agricultural and Stock Company, headquartered in a small general store in the middle of the 1280-acre ranch. In order to facilitate commerce, a small run of script notes bearing denominations of 5 cents, 10 cents, 25 cents, 50 cents and one dollar were produced by a Salt Lake City printing company. This script was used to pay colonists for their work and was subsequently traded by them to pay for goods and services at the store. In the rare occurrence that a settler needed to shop in Salt Lake City, the store would exchange cash for the script in the economy.

The losepa 50-cent note is the sole survivor, a single traveling trace of losepa and the commerce of the desolate spot. Signed by John T. Caine, treasurer of the cooperative and past editor of the Salt Lake Herald and Henry P. Richards, its president, the note exhibits characteristic wear of late 19th century paper, yet it is in surprisingly good condition when one considers the rigors it has been subjected to. Caine had served an LDS church mission to Hawaii in 1855 and after his tenure in losepa went on to be elected as a United States Representative while Richards played a major role in bringing Polynesian converts and their culture to the Salt Lake Valley.

losepa grew in spite of many trials, including the well-publicized cases of Ieprosy which struck three of the colonists in 1893. In order to contain the potential spread of the volatile disease, a house of isolation was built on the outskirts of town. To attract attention for the delivery of food and water, a flag was run up a pole as a signal. The town reached a maximum population of 228 late in the 19th century. It became an amalgamation of Polynesian and western cultures, with poi, island delicacies, and Latter-day Saint influences routinely mixing at public festivals. However, the continued hard lifestyle began to take its toll as the growth in the cemetery began to outstrip growth in the town. Many second-generation Hawaiians simply decided to leave losepa for more lucrative careers outside of the community. The town's death knell sounded when the construction of a new Latter-day Saint temple was announced in Hawaii. At first, a few settlers left to help in the building of the temple but a wholesale exodus followed in 1916-17. The motivation for living in the suffering climate of Utah was removed as members of the faith could now practice their religion fully in their own homeland, where it required substantially less consistent effort just to remain alive. The demise of the town occurred just four years after losepa was honored as the "Most Progressive Town in Utah" and it was finally taken over by the Deseret Livestock Company in 1917.

Visitors to the site in current times are no doubt greeted by the same skyline and landscape that threatened the dedicated and hardy Hawaiians in 1889. Little has changed. A small cemetery, some stone and shards of glass remain, along with a unique piece of paper with a quaint motto, redeemable for "an assortment of farm products at retail prices."

The losepa script note, a solitary specimen of a period of dynamic Utah history, continues today as the only artifact extant not subject to the wind, stinging sand, and drying sun of the Skull Valley area. In time, this small symbol may be all that exists to remind future historians of a little known town, fading into oblivion, that once was losepa.

by Bob Campbell

Salt Lake City, Utah